How employers are tracking employee office usage to inform design

The return to office is a work in progress, where employers try things one week and others the next.

In this quest to design the most efficient, user-friendly space for employees who come into the office just a few days a week, many have adopted technology that tracks occupancy, usage and dwell time. They’re analyzing that data and refining and tweaking work space and ergonomics.

That’s why the digital operations platform PagerDuty installed sensors from Density, a space analytics company, when it opened its new San Francisco headquarters last winter. The sensors — which look like white, plastic pucks — are powered by radar and machine learning to count people in unbound space. (There are no video cameras and they do not collect personal data.)

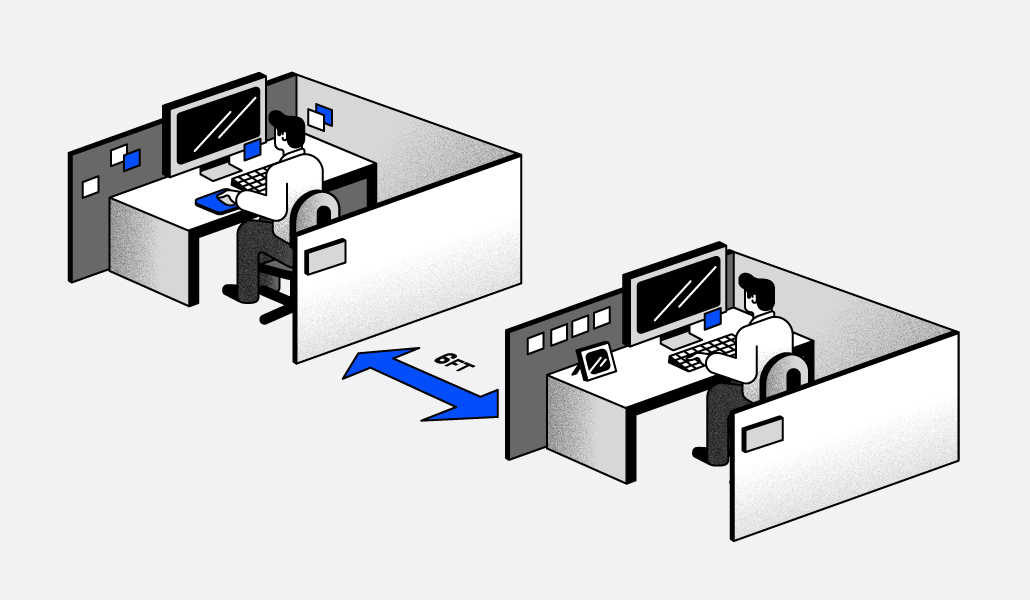

Yes, it’s able to count the number of people in each space and how long they spend there, but it’s also able to offer context. For instance, if an office space has a 100-person capacity and there are only 10 people working there, the utilization rate is just 10%. Likewise, if a conference room made for eight occupants typically only has four people meeting at a time, a company might decide to split the room into two, four-person meeting rooms.

Then there’s dwell time. If an employee books a desk through its hoteling software, it counts that the employee is at their desk for a day, right? Wrong. The person might arrive and check messages and do some heads-down work, then spend the rest of the afternoon in a collaboration area or a conference room. Knowing that, informs resources and space configuration.

“Dwell time lets us understand how a space is actually being used,” said Darren Graver, Density’s research lead. “If someone isn’t spending time there is it because they don’t have all the equipment they need? Is it because the chair is not ergonomic and it’s uncomfortable?”

It may just be that a company doesn’t need so many individual work stations.

“Employers want to know what their employees desire,” Graver said. “They want to provide a great experience and reduce that friction when employees are using the physical space.”

At PagerDuty, it helps inform decisions on everything from future real estate investments to workspace configurations to which technology to implement.

“We knew that things were going to change and that there were going to be experiments when we returned to the office,” said Nathan Manuel, senior manager of workplace experience at PagerDuty. “It’s also helping in future investments. What do we do when our lease ends? Do we actually need this much square footage?”

Another feature of the modern office is the smart locker, a necessity since so many companies aren’t offering permanent desks. Employees need a place to store the items they bring back and forth to work, particularly if they’re going several days per week. Many are turning to lockers that can be accessed with employee I.D. cards or cell phones to cut down on touch points, optimize privacy and ease of use.

At Modern Office Systems, pre-pandemic locker sales were 25% of its business, according to Jim Maywalt, director of business development. Today it’s 75%.

“It’s the only home base most employees have at the office,” said Maywalt.

These digital lockers provide employers with usage metrics. That data helps guide employers on how many lockers they need and whether to assign them permanently to one person or keep them available for individual use.

These technologies are helping companies save money. When it comes to lockers, businesses are advised to start small and consult usage data before installing more. At offices, employers are using data to determine which days tend to have lower occupancy and use that information to reduce supplies like food orders and cleaning crews.

“There’s no use having a janitor clean an entire floor if it’s been empty all day,” Graver said.

It’s also helping refine employee preferences. For example, Density’s Graver pointed to one client who conducted an A/B test to determine which video conferencing service was preferable to employees by equipping one conference room with Zoom and the other with Google Meet. The occupancy numbers helped them decide which video conference service to use.

“These are all the things that help drive employee experience,” said Graver.

3 Questions with Janet Stovall, senior client strategist, NeuroLeadership Institute

It’s been nearly two years since the murder of George Floyd galvanized the corporate world to take more action to improve diversity, equity and inclusion. Are you confident that momentum has maintained?

There’s a continuum of how companies are dealing with it. So right after the murder, most companies stepped in and said we’ve got to do something. Now things are settling back. And in some places, they’re regressing, because change is not something we’re comfortable with. And rapid change is something we really aren’t comfortable with. Inequity is systemic, not something that individuals can control. And systemic systems don’t change easily. So you’ve got companies that leaned into it and they are increasingly more sophisticated in what they’re looking for, in terms of DEI, and they’re impatient to change it. On the other end, you have companies that are going backwards, who say: that was too much too fast, we don’t want to do it, or we did that but we’re going to stop. And then you have the ones in the middle, who really don’t quite know what to do. They don’t want to go backwards, but they don’t want to go forward too fast.

What impact has the pandemic had on DEI?

Covid has driven a new focus on the DEI space, especially the E — the equity part. Covid taught us that systemic inequity was a real thing, because we saw what it meant for people who are different economic levels, different races, different genders, and the fallback that has come from that for women, for people of color, for people in frontline jobs — who are often women and people of color. We saw the inequity, and it’s systemic. We have talked about inequity as a personal interpersonal issue for some time, you know, people being not fair to each other. But the reality is, it’s a systemic problem so it needs systemic solutions, but systemic solutions start at the interpersonal level. And that’s where the brain gets involved in how you view equity, how you view fairness, how you view bias, all those things, it starts in the brain.

Proximity bias gets mentioned a lot as the new challenge for inclusive corporate cultures in this new hybrid-working norm. How big a concern is it?

When we come back into the offices, there are going to be people who don’t want to go back for a lot of reasons. And some of it has to do with bias — they dealt with similarity biases, they dealt with threat states in this space. And they’ve got out of it [by working remotely]. They’re like, ‘you know what, this is great, I don’t want to go back to that.’ So organizations are going to have to decide whether they lean in to that distance bias, or if they intentionally fight against that, because it’s going to kick in. It was an issue even when we were all separate, there was an issue about who came back first. And we’re creating sort of a new hierarchy, the people who want to be in the office versus those who don’t.

So a lot of people want to go back, but we’re creating two different classes of people because of our bias, because the reality is the people who want to work at home have very good reasons for that. But our bias means that the people who are may be viewed differently. So we’re creating new “in” and “out” groups. It used to be maybe that the in-group was all the top white guys. Now the in-groups may be those who are in the office versus those who are out, and all the issues of psychological safety, all the issues of similarity bias, they’re going to play out now on a different field. — Jessica Davies.

By the numbers

- 66% of 5,000 working women across 10 countries, who work in a hybrid environment, said they are significantly more likely to experience microaggressions than those who work exclusively on site (34%) or exclusively remote (41%).

[Source of data: Deloitte report.] - Google searches for “toxic work environment quiz” increased 700% in April.

[Source of data: Conductor data.] - 10% of 3,000 U.S. workers polled said they work naked or partially naked every single day, while another 55% admit to wearing just their underwear while working.

[Source of data: Shinesty report.]

What else we’ve covered

- More Big Tech talent is moving into edtech, as they seek roles that better align with their values and sense of purpose, in the wake of the pandemic.

- Part of the reason hybrid working policies are a mess is that workforce strategies have been centered on where employees should be while they work, rather than on work outcomes.

- People are increasingly returning to the workplace after retiring a year before – a trend that’s been dubbed “unretirement.”

- People’s priorities and work styles have shifted to such an extent over the last two years, that learning what employees value and what motivates them has become more critical than ever to retaining them. A lot of it boils down to personality type.

- Back-to-back meetings are not uncommon, but people are finding it’s impossible to crack on with their day job when their diary is full of meetings. That’s why some companies have banned meetings entirely.

- Employers are appealing to people’s stomachs in a bid to entice them back to the office. Though hybrid work arrangements have made supplying lunch more complicated.

- Reverse mentorship could be a remedy to the Great Resignation and companies holding on to disaffected younger generations of workers.

What we’re reading

- For leaders committed to creating more equitable cultures within their companies, it’s imperative to reflect on when they may have been complicit in suppressing staffers’ contributions, particularly for women of color [Toolkits.]

- The rise of ‘power casual’: Retailers that once trafficked in solidly reliable dresses are scrambling to cater to the new demands of the hybrid workweek [New York Times.]